Wall Street was caught off guard when the Commerce Department reported yesterday morning that orders for durable goods — big items like home computers and factory machines — plunged almost 8 percent last month. That’s a big number, but it really shouldn't have come as too much of a surprise. In two of the last three months, the manufacturing sector has shrunk, according to surveys by the Institute for Supply Management that have been out for weeks.

**NOTE: I won't always be focusing this much on the economy, but with the big news out of Wall Street yesterday, it seems appropriate to give it some more attention and explain what's going on with the economy itself.**

Most Americans don't really 'get' the economy. They see the price of a gallon of gas or the changing mortgage rates as either out of man's hands or manipulated by corporate overlords.

Best case scenario, we were forced to take a semester or two of economics in college. Which we promptly forgot.

This is the first in what will be an ongoing series of posts exploring what the hell economic news means. The nightly recap of the Dow and Nasdaq tosses mention of trade deficits or consumer confidence without any look at why that caused those Wall Street traders to yell and hustle.

Manufacturing

A country's manufacturing industry is the basis for its wealth. It turns raw materials into something of use for consumers or other businesses. Even in a highly internationalized economy, it is impossible to imagine a large country prospering without some kind of healthy factories.

What would be the basis for the money to pay for the services offered by other companies? To buy all that crap down at Wal-Mart? Creating things is the clear foundation for wealth; the rest of the economy multiplies that base.

American manufacturing has been in trouble for a long time. With lower prices and fresher designs, foreign competitors decimated their domestic counterparts. For their part, corporate executives failed to see changes in consumer preference and were blindsided by more nimble foreign firms. This process started with the Japanese three decades, but has dramatically intensified with the full-scale entry of China into the world market.

However, we have managed to maintain respectable durable goods industries, such as automobiles, factory equipment, and furniture. These are larger, more long-lasting items that often require more high technology input and manufacturing techniques.

Any change in demand for durable goods is an indicator of how the consumer at large is thinking. If they are economically uneasy, they will postpone those big purchases until times are better.

Capital goods are a subset of durable goods. They only refer to goods purchased by other firms as investment in their business, such as factory or heavy construction equipment (think of a big, yellow bulldozer).

If business isn't buying capital goods, they don't think they have to expand. Basically, business is pessimistic about the future.

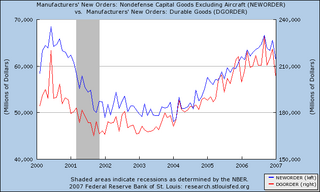

Check out this graph of capital goods (blue, left axis) and durable goods (red, right axis). The shaded section is the 2001 recession.

Although they generally move together, durable goods are much more volatile than capital goods; business is better at planning ahead than people are individually.

Although they generally move together, durable goods are much more volatile than capital goods; business is better at planning ahead than people are individually.Until recently, this facet of the economy was humming along. Just as this hasn't meant that the wider economy was doing well, a downturn in the manufacturing sector isn't necessarily disaster.

However, as the New York Times notes:

For months now, the economy seemed to shrug off the forces weighing on it and just kept on growing. But those forces never went away. If anything, a number of them have gotten worse. And that’s the most worrisome part of the bad news from the nation’s factories: it fits into a larger story.

The sudden, major fall off in durable goods is worrying; the fall in capital goods more so.

(Hat tip to Menzie Chinn at Econbrowser)

1 comment:

Econ is the new Blog

Post a Comment